Last night, while scrolling, I stumbled across a set of images about congenital heart disease. I was not looking for them. They simply appeared. And if I am really honest, they were about the last thing I needed to see after a day of watching appointment after appointment populate my hospital’s patient portal, while also grappling with the heavy emotions of transplant evaluation, again.

What surprised me most was how upsetting they were, even now, even after decades of living with congenital heart disease as an adult. I still carry a familiar tension. I need support, and I also worry deeply about asking for too much of the people who love me. Those two things have always lived side by side in my body. Seeing these images brought that conflict straight to the surface.

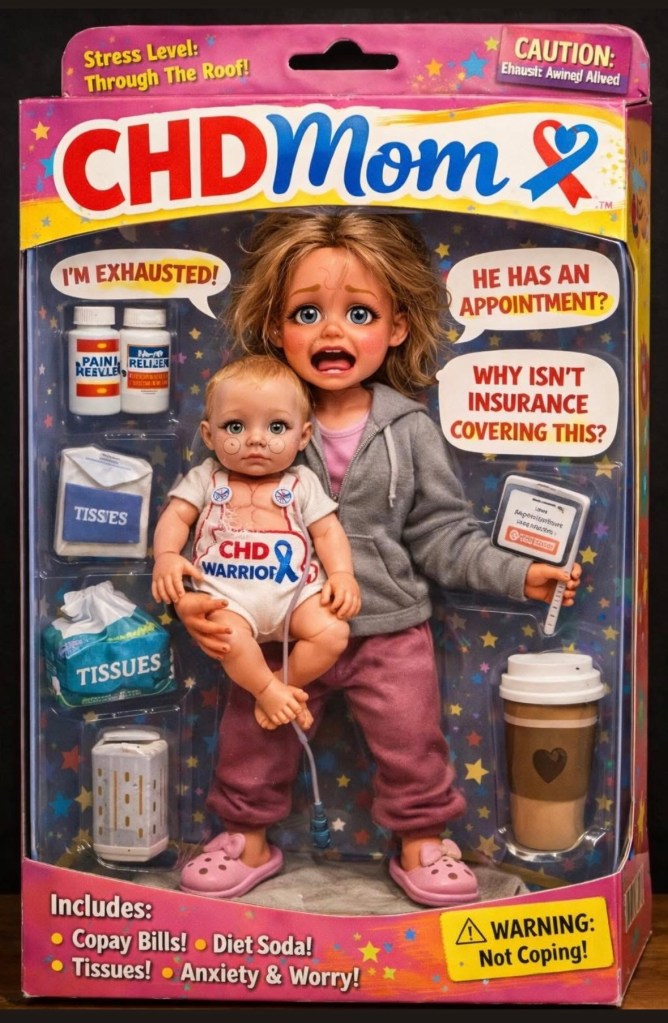

It turns caregiving into spectacle and quietly positions the child as the source of stress, fear, and burnout.

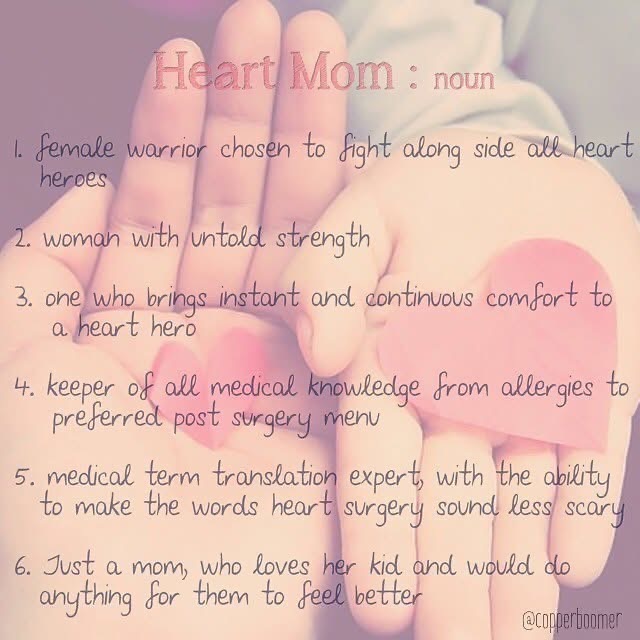

I want to be clear about why images like these are damaging, and about the difference between what a “heart mom” or “heart dad” might see, versus what a person living with CHD sees.

I am a 43-year-old adult living with congenital heart disease. I grew up as the child everyone worried about, planned around, and tried to protect. Children with CHD learn very early to read the room. We learn to track tone, tension, and fear long before we have language for what is happening inside our own bodies.

Many of the recent AI-generated “awareness” images circulating online depict parents crushed under the weight of CHD. They show caregiving as collapse, exhaustion, and spectacle. Even when shared with good intentions, they carry a powerful implied message for the child at the center of the story.

You are the weight.

You are the cost.

That message sticks.

I know this because I have lived it. When I was a child, my father once joked that I was “more trouble than I was worth.” He did not intend harm. It was meant facetiously, a throwaway comment. But it landed squarely on one of my greatest fears. I internalized it, and I have been unpacking the impact of those words in my life, including in therapy, for the last 30 years.

Children with heart disease already worry about how much they ask of the people who love them. They already carry guilt that is not theirs. Vacations cancelled. Trips cut short. Bills expanding. Time off work dwindling. Over the years, through my time with kids at heart camp, I have seen this weight show up again and again. Children worrying about being too much. About causing stress. About being the reason someone else is tired, overwhelmed, or afraid.

This is why these images matter.

I have created CHD-related graphics myself in the past. I believe there is a meaningful difference between imagery that centers care, advocacy, and love, and imagery that turns the child into the source of suffering. Framing matters. Symbolism matters. What we choose to emphasize shapes how children understand themselves.

Content that frames illness as something a parent endures because of a child does not raise awareness for that child. It quietly teaches them that their existence is what broke someone else, often the very person they turn to for comfort and care. A parent should be standing beside their child in the fight, not cast as someone crushed by them. A child’s heart condition is part of who they are, but it is not all of them, and it should never be treated as the most important part, even when it demands the most attention.

This kind of framing does not stop with images. It shows up in the language we use, too. Do not even get me started on the label “heart warrior.” I understand why people reach for it, and there are times it IS empowering. It is meant to honor resilience however, timing and situation are key. But for many of us, it carries an unspoken pressure to be brave at all times, to endure without complaint, and to make our suffering palatable to others. When you are called a warrior, fear starts to feel like failure. Grief feels like weakness. Needing rest, softness, or support can feel like letting people down. Children absorb that too. They learn quickly that being loved is tied to being strong, even when they are exhausted, scared, or in pain.

All of this is why these conversations feel so fraught, especially when they happen in public. We are not just reacting to a single image or a single word. We are responding to years of messaging that asks children to carry guilt quietly and to perform strength and bravery convincingly.

When I tried to engage with the person who created these images, my response was not as constructive as it could have been. I was reacting from a place of hurt, and I wanted to give some of that hurt back. It was not my best moment. At the same time, my lived experience was dismissed rather than heard. That dismissal is something many people with chronic illness or disability encounter repeatedly.

We are often asked for our insight or guidance, only to have our reality rejected because it is uncomfortable. Because it does not allow others to pretend nothing is or can go wrong. Or because it requires seeing a child as a whole person who needs many kinds of care, not just care for their disease.

Honoring parents and acknowledging how hard caregiving can be does not require turning children into symbols of burden, martyrdom, or collapse. I truly believe that parents of sick children are incredible. They do carry a great deal of weight, and they deserve to be honored and supported. But not because they are surviving their child. Because they are fighting alongside them. Because they know how to make the moments better, even when they cannot fix the illness.

I want these parents to be proud of what they do. I am deeply proud of my own mother and everything she has faced with me. That is exactly why images like these hurt.

There are other ways to tell this story. Picture yourself not as someone crushed under the weight of your child’s illness, but as someone standing beside them, clearing a path. A parent whose coffee fuels vigilance and care. Whose notebook of symptoms and questions is not evidence of collapse, but a tool of advocacy. Not a martyr, not a survivor of their child, but a partner in the fight.

I believe most people share images like these with good intentions. I am simply asking that as CHD Awareness Month approaches, we also consider their impact, especially on the children who grow up absorbing these messages long before they have the words to question them. Their feelings and well-being deserve to remain at the center of our advocacy.